An Engineer / Not a Camera

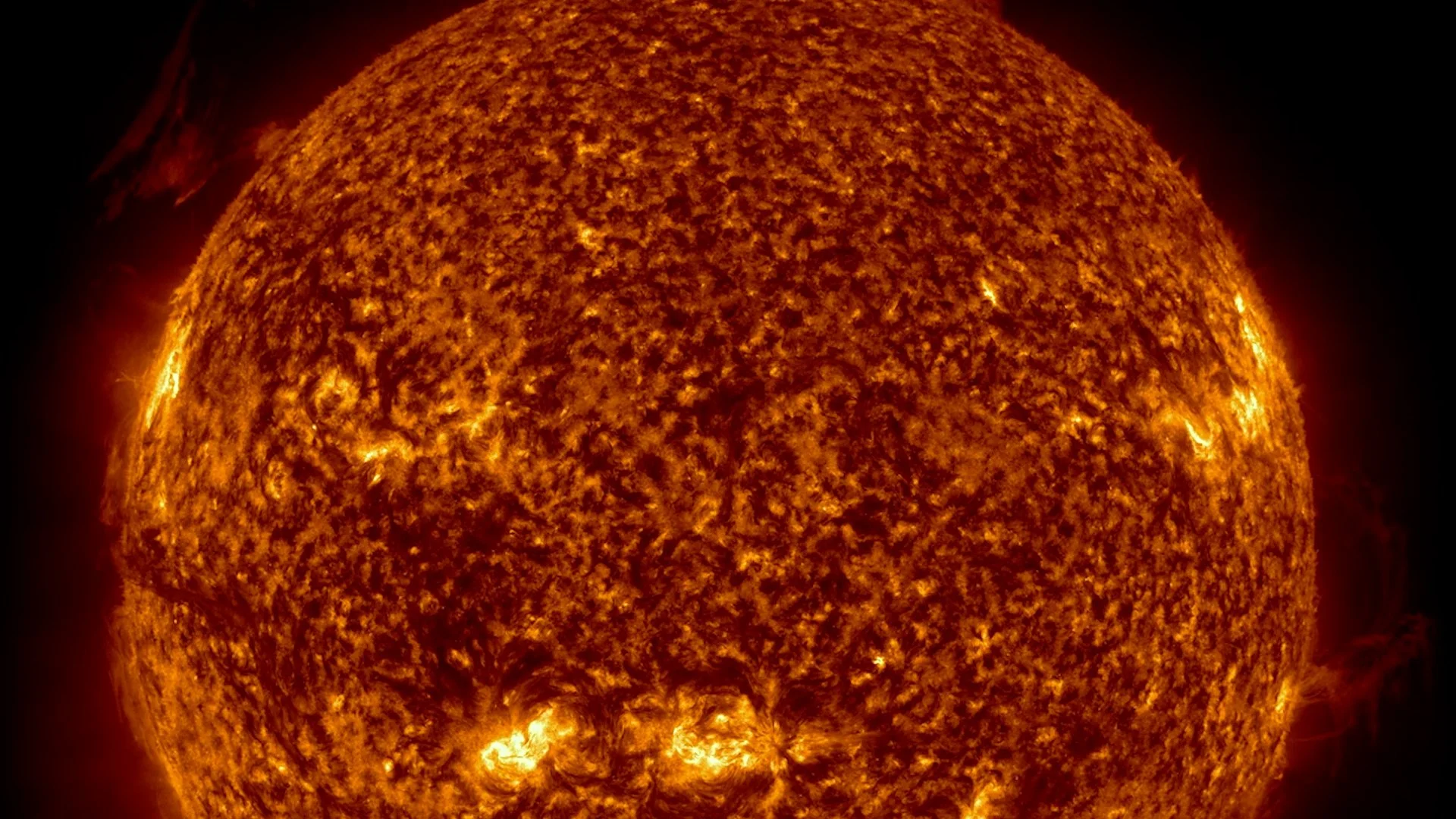

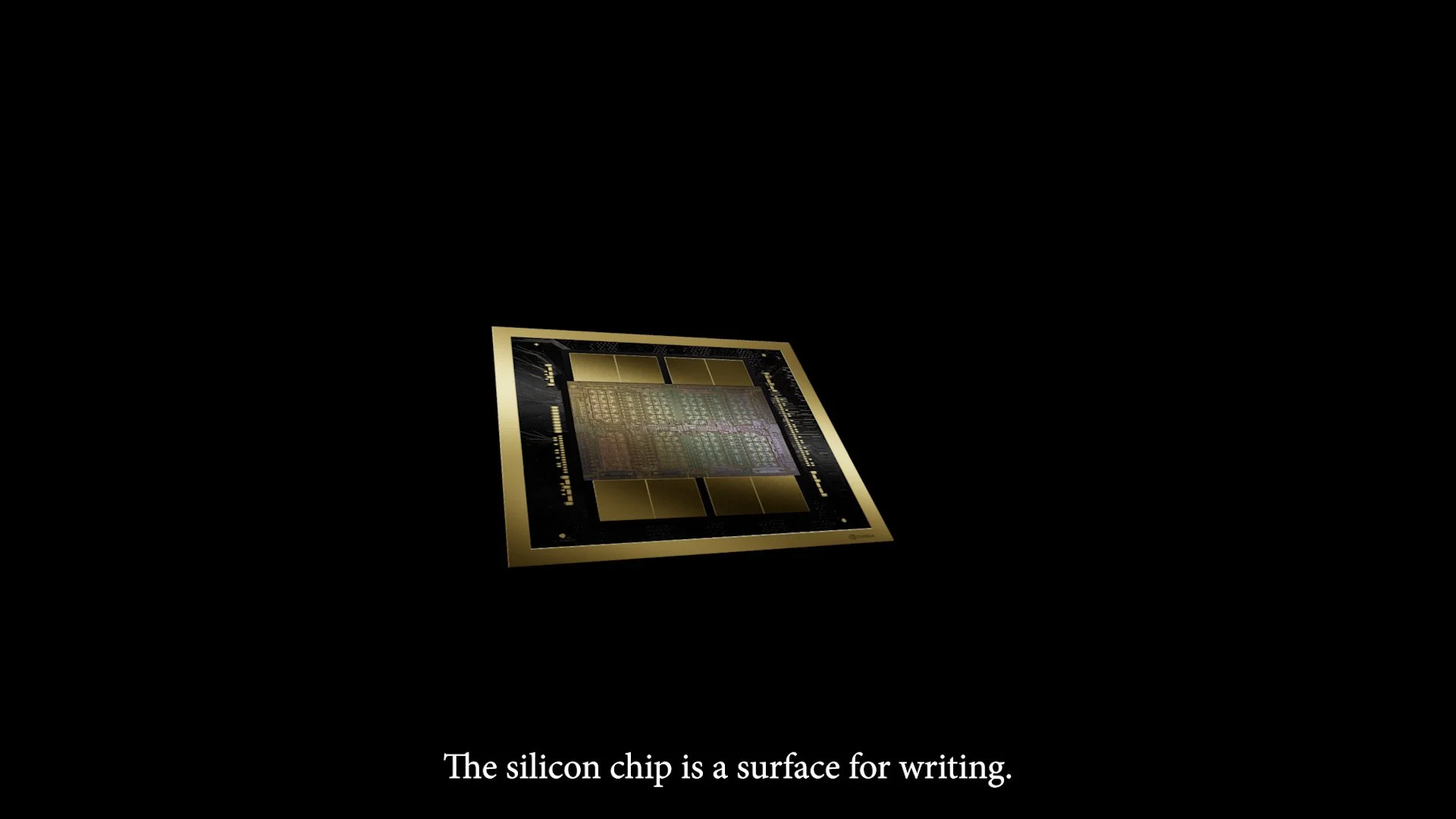

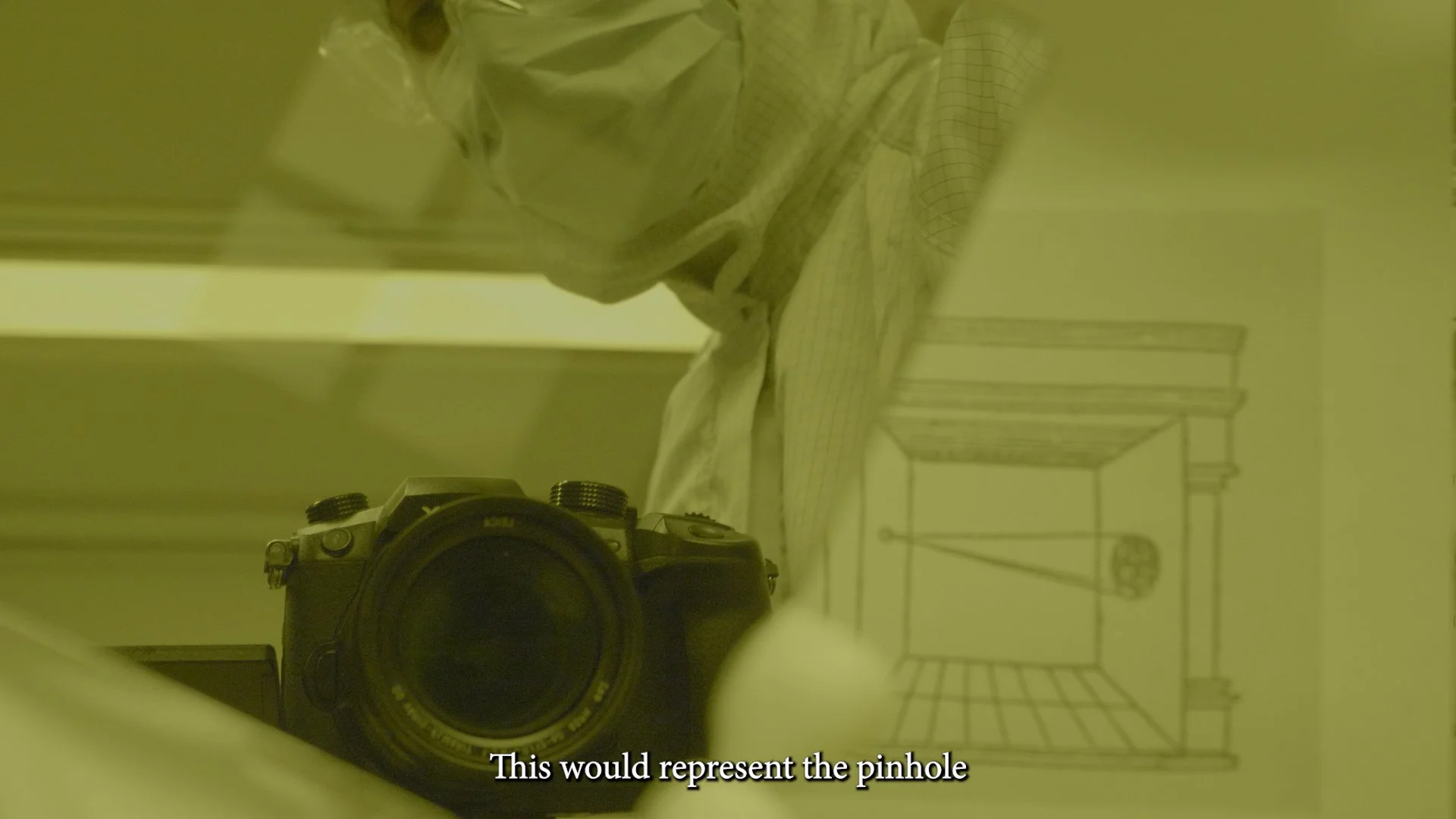

The production of a computer chip is perhaps the most complex technical process in human history. But at the heart of this cutting-edge technology shaping the future are the older sciences of photography and optics that date back centuries. In 1827, the French inventor and engineer Joseph Nicéphore Niépce developed what is widely considered the first photoresist, which he successfully used to capture a fixed image of the world with sunlight and the principles of a camera obscura. He called this image a heliograph, or "sun drawing." Half a century later, the English photographer and engineer Eadweard Muybridge advanced these methods to capture and observe the motion of Leland Stanford's prized racehorses. By the mid-twentieth century, the American industrial laboratory Bell Labs adapted and patented a version of this process called photolithography for the fabrication of semiconductor microchips. In this timeline, Niépce’s nineteenth-century heliograph becomes the antecedent to Donna Haraway’s microchip made of sunshine at the end of the twentieth century. “The new machines are so clean and light,” she wrote in 1985, “their engineers are sun-worshippers mediating a new scientific revolution associated with the night dream of post-industrial society.” Decades into the reality of this dream, AI and computer-generated imagery are almost indistinguishable from those made with a camera. Once a method for capturing an image of the world, the principles of optics are now being used to build machines that can make images of the world without needing to see it. Muybridge’s galloping horse turns from motion to be captured, to data to be rendered. As this new virtual world grows richer, the allure of escaping into this elsewhere grows with it. Yet there is no elsewhere. Every image that beckons from an uncanny world somewhere else fundamentally alters our world right before our eyes.

Trailer